Project #4 - Concurrency Control

Do not post your project on a public GitHub repository.

Overview

In this project, you will add transaction support for BusTub by implementing optimistic multi-version concurrency control (MVOCC). The project consists of four tasks, two optional bonus tasks, and one leaderboard benchmark.

- Task #1 - Timestamps

- Task #2 - Storage Format and Sequential Scan

- Task #3 - MVCC Executors

- Task #4 - Primary Key Index

- ★Bonus Task #1 - Abort★

- ★Bonus Task #2 - Serializable Verification★

This project must be completed individually (i.e., no groups). Before you start, please run git pull public master and rerun cmake to reconfigure the Makefile.

- Release Date: Nov 13, 2023

- Due Date: Dec 10, 2023 @ 11:59pm

Project Specification

Like previous projects, we provide classes that define the APIs you must implement. Do not modify the signatures of the predefined functions or remove predefined member variables in these classes unless indicated; if you do, our test code will not work and you will receive no credit for the project. You may add private helper functions and member variables to these classes as needed.

The correctness of this project depends on the correctness of your implementation of Projects #1 and #2. You may get a full score in this project without a complete implementation of Project #3 as we will rewrite most of the access method executors based on MVCC storage. A working implementation of sequential scan to index scan optimizer rule is required for Task 4.2. A working aggregation executor from Project #3 is required to complete the leaderboard test in this project. We do not provide solutions for previous projects, except the hash table index wrapper we provided in Project #2.

In this project, you will implement multi-version concurrency control in BusTub. The same protocol has been used in several industry/academia systems ([1], [2]). The storage model is similar to the delta table in the lecture. We store the undo log deltas in each transaction’s private space called undo log buffer. The tuple in the table heap and its corresponding undo logs form a singly-linked list, so-called version chain.

At the minimum you will implement the SNAPSHOT ISOLATION level for transactions. There is an optional extension to add support for SERIALIZABLE isolation level in Bonus Task #2. All transactions in one test case will run in the same isolation level. All concurrent test cases are public, and all hidden test cases run in a single thread. On Gradescope, you will find the description of what each test case is testing.

This project has two score boundaries.

- If you implement the MVCC protocol correctly, you will get a total of 80 points. There will be only one concurrent test case up to the 80 point boundary.

- To further get a total of 100 points, you will likely need to spend as much time finishing all tasks of the 80 points boundary.

- To further get the 20 bonus points, you will likely need to spend as much time finishing all the required tasks.

You can use late days for the bonus tasks if you still have some left, but late days are not allowed for leaderboard tests.

Task #1 - Timestamps

In BusTub, each transaction will be assigned with two timestamps: read timestamp and commit timestamp. In this task, we will walk through how the timestamps are assigned, and you will need to implement the transaction manager to assign timestamps correctly to transactions.

1.1 Timestamp Allocation

When a transaction begins, it will be assigned a read timestamp, which is the commit timestamp of the latest committed transaction. On transaction commit, it will be assigned a monotonically-increasing commit timestamp. The read timestamp determines what data can be read by a transaction, and the commit timestamp determines the serialization order of the transactions.

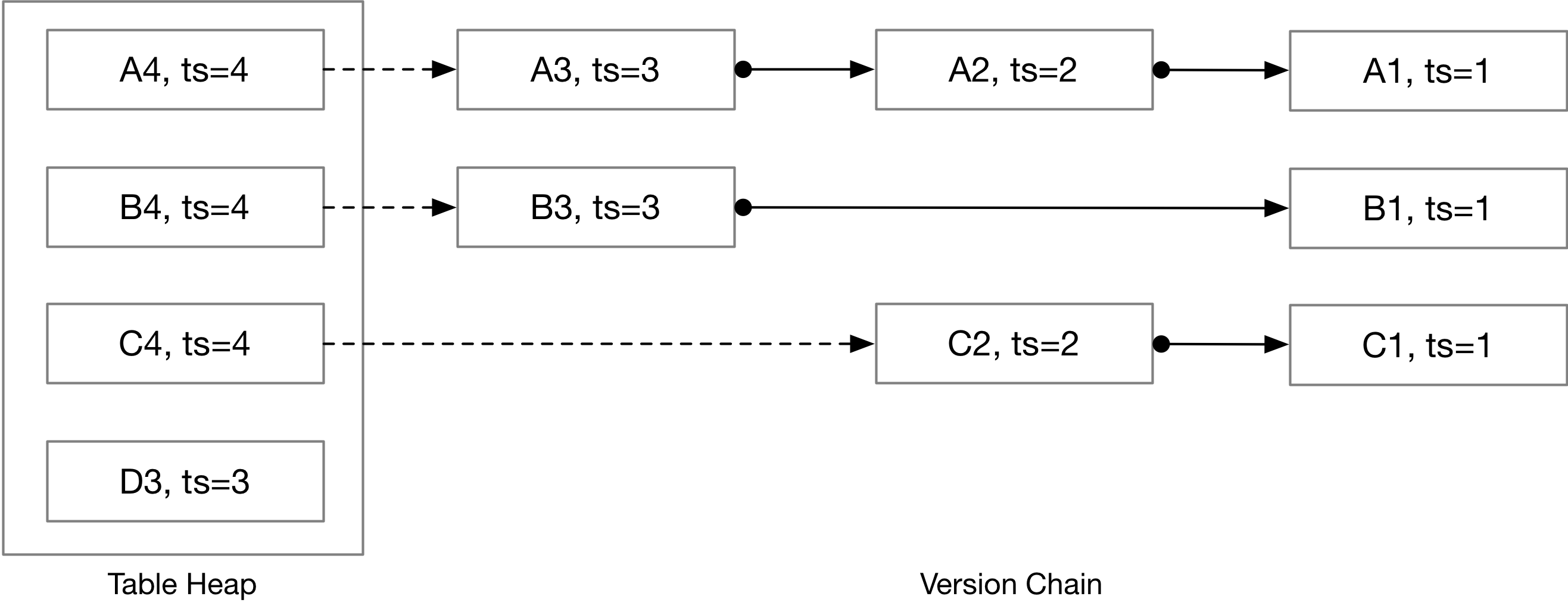

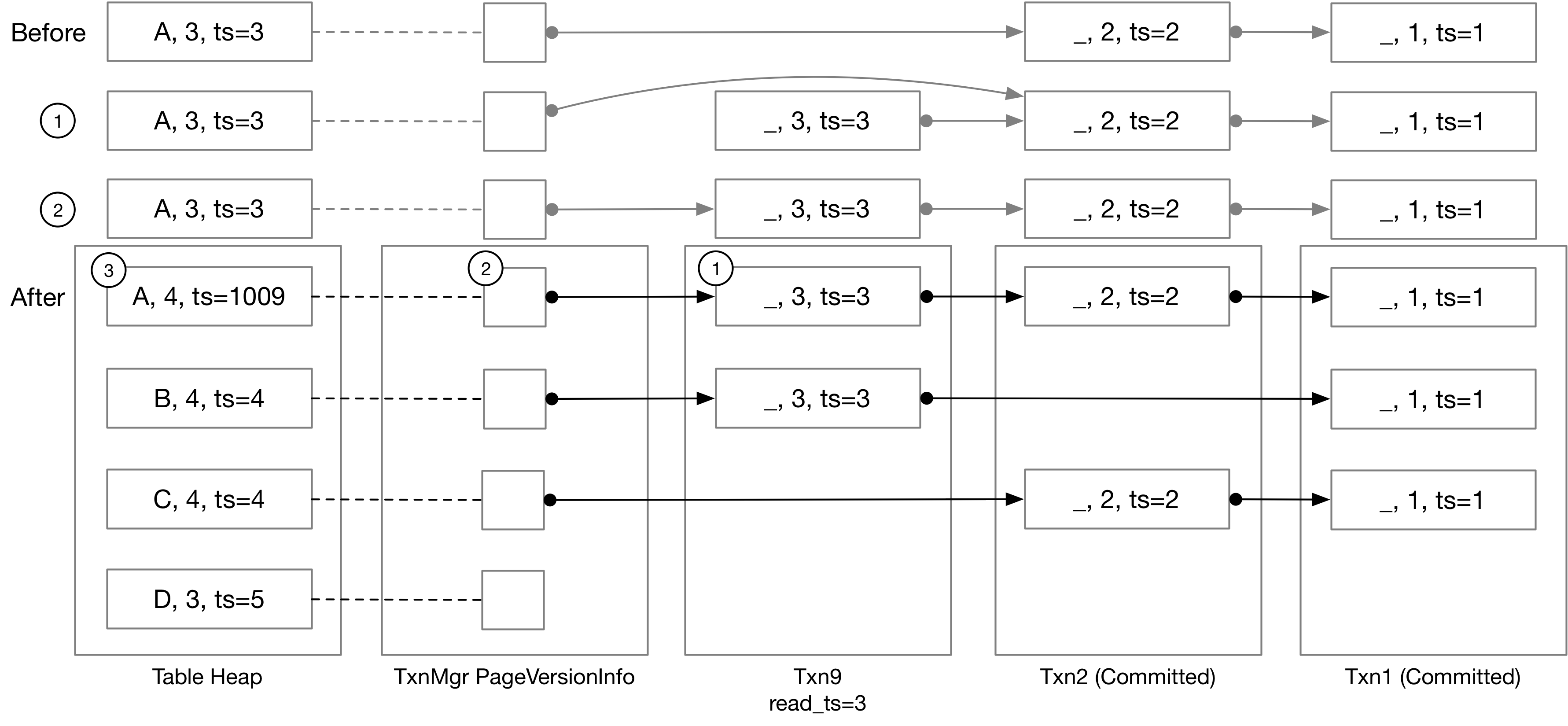

We will explain the read timestamp with the following example. Assume that we have 4 tuples in the table heap.

Read timestamp determines the version the current transaction can see. For example, if we have a transaction of read timestamp = 3, it will see A3, B3, C2, and D3 in this example. If read timestamp = 2, it will see A2, B1, C2. When a transaction begins, the read timestamp will be the timestamp of the latest committed transaction, so that the transaction will be able to see everything committed before the transaction begins.

Commit timestamp is the time that a transaction commits. It is a logical counter that increases by one each time a transaction commits. The DBMS will use a transaction's commit timestamp when it modifies tuples in the databases. For example, the D3 tuple is written by a transaction with a commit timestamp of 3.

You will need to assign the transactions with the correct read timestamp and commit timestamp in this task. See TransactionManager::Begin and TransactionManager::Commit for more information. We already provide the starter code for TransactionManager::Abort, and you do not need to change anything in Abort in order to get full points in Task #1.

1.2 Watermark

Watermark is the lowest read timestamp among all in-progress transactions. The easiest way of computing the watermark is to iterate all transactions in the transaction map and find the minimum of read_ts among all on-going transactions. However, this simple strategy is not efficient. In this task, you will need to implement an algorithm of at least O(log N) time complexity to compute the watermark of the read timestamp in the system. Please refer to watermark.h and watermark.cpp for more information. You will also need to call Watermark::AddTxn and Watermark::RemoveTxn when a transaction starts / commits / aborts.

There are many ways to achieve it: using a heap or using std::map. The reference solution implements an amortized O(1) algorithm using a hash map.

You should pass all test cases in the TxnTimestampTest suite at this point.

Task #2 - Storage Format and Sequential Scan

BusTub stores transaction data in three places: table heap, transaction manager, and inside each transaction. The table heap always contains the latest data, the transaction manager “page version info” stores the pointer to the next modification, and inside each transaction, we store the tuples that the transaction modified, in a format called undo log. To retrieve the tuple at a given read timestamp, you will need to (1) fetch all modifications (aka. undo logs) that happen after the given timestamp, and (2) apply the modification (“undo” the undo logs) to the latest version of the tuple to recover a past version of the tuple.

This is similar to the delta table storage model that we covered in the lectures, except that there is no physical “delta table” to store the delta records. Instead, these records are stored within the private space of each transaction, not being persisted on the disk, so as to simplify the implementation and boost efficiency.

2.1 Tuple Reconstruction

In this task, you will need to implement the tuple reconstruction algorithm. You will need to implement the ReconstructTuple function. The function is defined in execution_common.cpp. Throughout the project, you will find that some functionalities can be shared by different components in the system, and you can define such functions in execution_common.cpp.

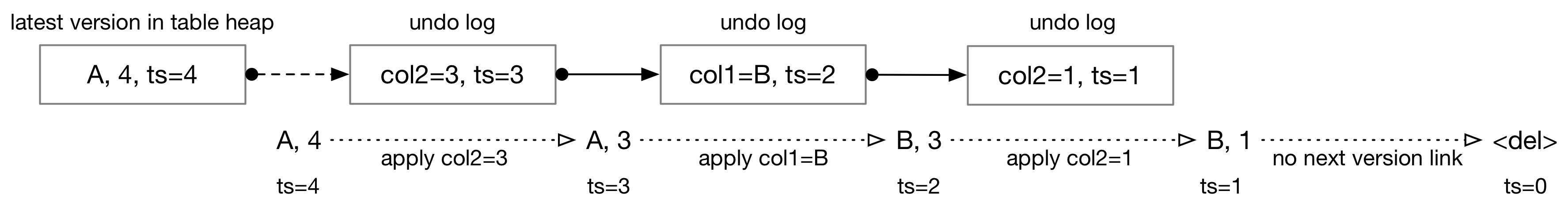

ReconstructTuple takes a base tuple and base metadata stored in the table heap, and a list of undo logs in descending order of the time they are added to the system. Here is an example of reconstructing a tuple.

Base tuples always contain full data. Undo logs, however, only contain the columns that are changed by an operation. You will also need to handle the case that the tuple is removed by examining the is_delete flag in both undo logs and table heap.

ReconstructTuple will always apply all modifications provided to the function WITHOUT looking at the timestamp in the metadata or undo logs. It does not need to access data other than the ones provided in the function parameter list.

The undo log contains a partial update. modified_fields is a vector of bool that has the same length as the table schema. If one of the fields is set to true, it indicates that the field is updated. The tuple field contains the partial tuple. To retrieve a value from the tuple, you will likely need to construct the partial schema of the tuple based on the table schema and the modified fields. The timestamp is the read timestamp that this undo log corresponds to. We also store a link to the next undo log, and if this is the last undo log in the chain, TxnId will be set to INVALID_TXN. Again, you do NOT need to examine the timestamp field and the previous version field in ReconstructTuple.

2.2 Sequential Scan / Tuple Retrieval

In this task, you will need to rewrite your sequential scan executor from Project #3, so as to support retrieving data from the past based on the read timestamp of a transaction.

The sequential scan executor scans the table heap, retrieves the undo logs up to the transaction read timestamp, and then reconstructs the original tuple that will be used as the output of the executor. There are 3 cases you will need to handle in the MVCC sequential scan executor.

- The tuple in the table heap is the most recent data. You can know this by comparing the timestamp in the table heap tuple metadata and the transaction the read timestamp. In this case, the sequential scan executor may directly return the tuple, or skip the tuple if it has been removed.

- The tuple in the table heap contains modification by the current transaction. In BusTub, a valid commit timestamp ranges from 0 to

TXN_START_ID - 1. If the highest numerical bit of a timestamp is set to 1 in the table heap, it means that the tuple is modified by a transaction and the transaction has not been committed. We call this timestamp a “transaction temporary timestamp”, which is computed byTXN_START_ID + txn_human_readable_id = txn_id. The first transaction id in BusTub isTXN_START_ID. This is a very large number which is hard to interpret, and therefore we can generate a human-readable id by stripping the highest bit. We will usetxnX, where X is the human-readable id, in the following examples. Undo logs will never contain transaction temporary timestamps (we will explain it in later sections). For example, if the current transaction human-readable id is 3, and it scans a base tuple with timestampTXN_START_ID + 3, then this tuple is modified by this transaction, and it should be directly returned to the user. Otherwise, the transaction should recover a past version of this tuple and return it to the user. - The tuple in the table heap is (1) modified by another uncommitted transaction, or (2) newer than the transaction read timestamp. In this case, you will need to iterate the version chain to collect all undo logs after the read timestamp, and recover the past version of the tuple.

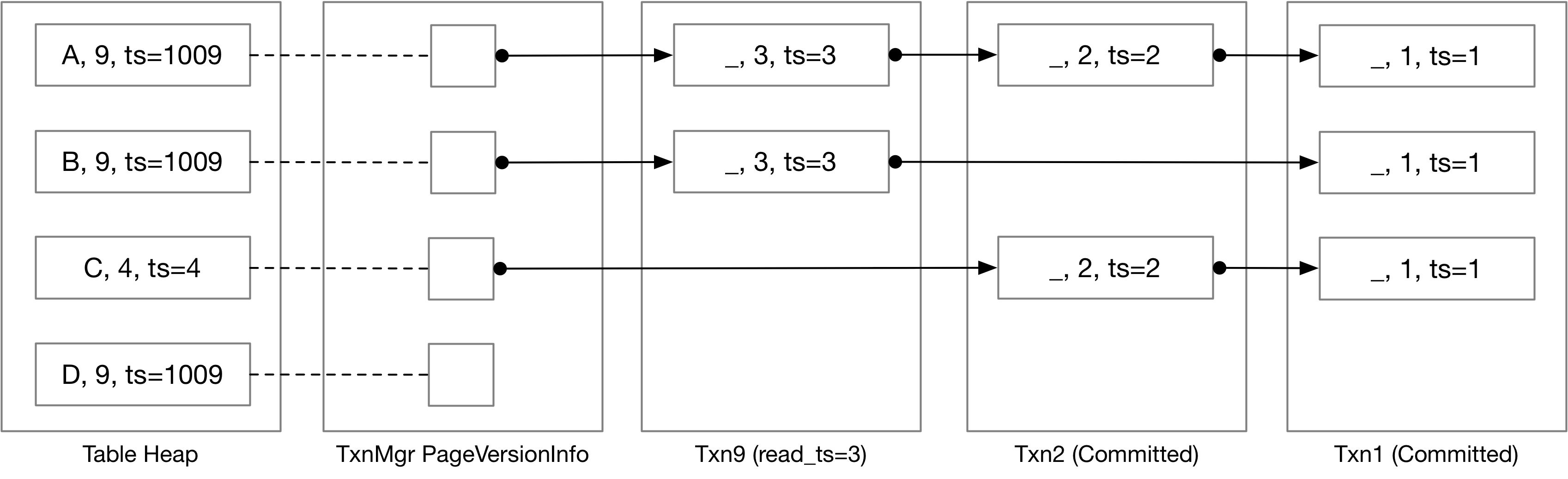

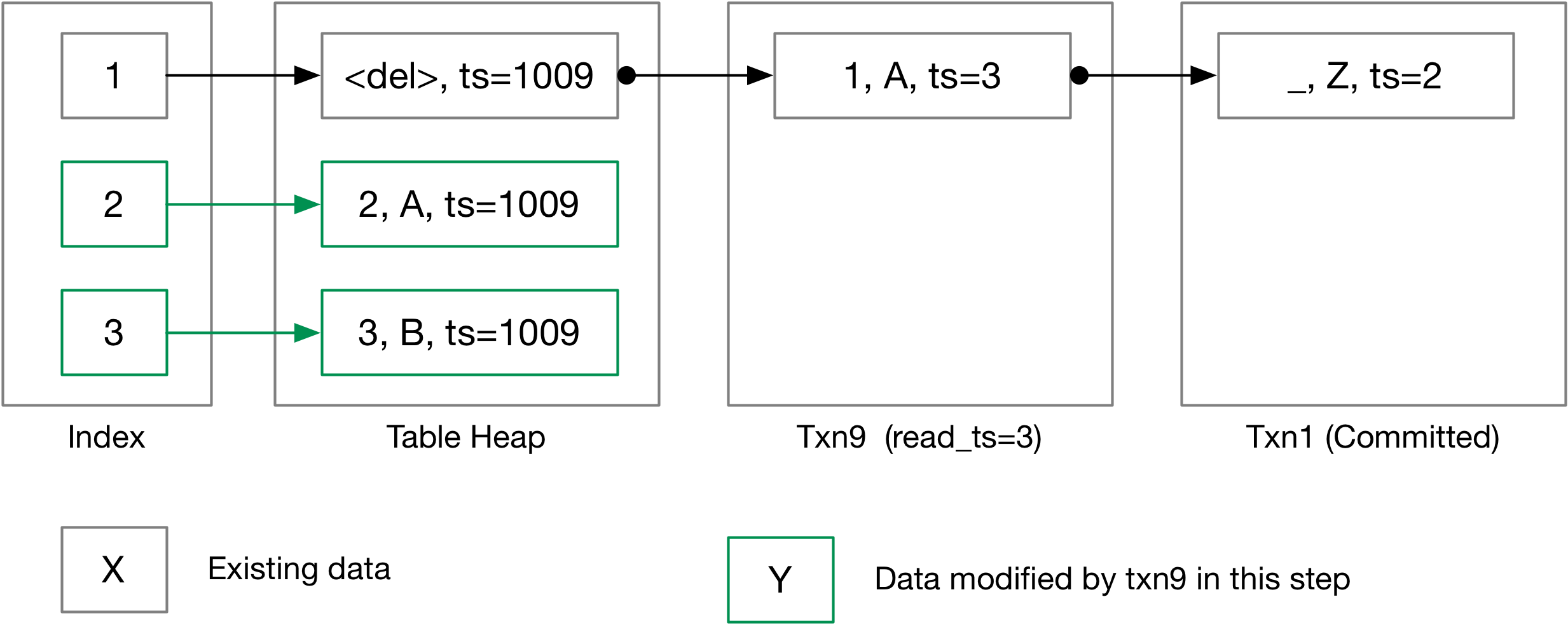

To make our illustration easier to understand, TXN_START_ID in the below example will be 1000. Therefore, 1009 indicates the tuple contains an uncommitted update of txn9.

Next, let us take a look at the following example, where we traverse the version chain to collect the undo logs and construct the tuples that the user requests.

Txn9 is not committed yet and the read timestamp is 3. The result of a sequential scan in txn9 of the table will be: (A, 9), (B, 9), (C, 2), (D, 9). For (A, 9), because the table heap contains the uncommitted update of txn9, we can directly send it to the parent executor. For (C, 2), as the read timestamp is 3, we can know that the table heap contains a later update, and we will need to traverse the version chain to recover an older version.

Consider another transaction that has a read timestamp of 4. The result of a sequential scan of this transaction will be: (A, 3), (B, 3), (C, 4). For (A, 3) and (B, 3), the table heap contains a pending update, so we will need to traverse the version chain to get the last update before/at timestamp 4. As the first undo log is at timestamp 3, which indicates the last update before timestamp 4 is at timestamp 3, we only need to retrieve that one. (C, 4) is the latest update at read timestamp 4. (D, 9) is a pending update by another transaction, and it does not have a version chain yet, so we do not need to return it to the user.

To retrieve the undo log link from table heap to the first undo log, you can use the GetUndoLink function in the transaction manager. There is another function called GetVersionLink that returns more information about the version link, which will be useful starting Task 4.2.

The example is oversimplified compared with the test cases. You will also need to think about null data and data types other than integer when implementing the sequential scan executor.

Our test cases will manually set up some transactions and the table heap content, so that you do not need to implement insert executors to test your sequential scan implementation. At this point, you should pass all test cases in TxnScanTest.

Task #3 - MVCC Executors

In this section, you will need to implement data modification executors, including insert executor, delete executor, and update executor. Starting from this task, your implementation will not be compatible with project 3, as we only support schema of fixed-size data types.

3.1 Insert Executor

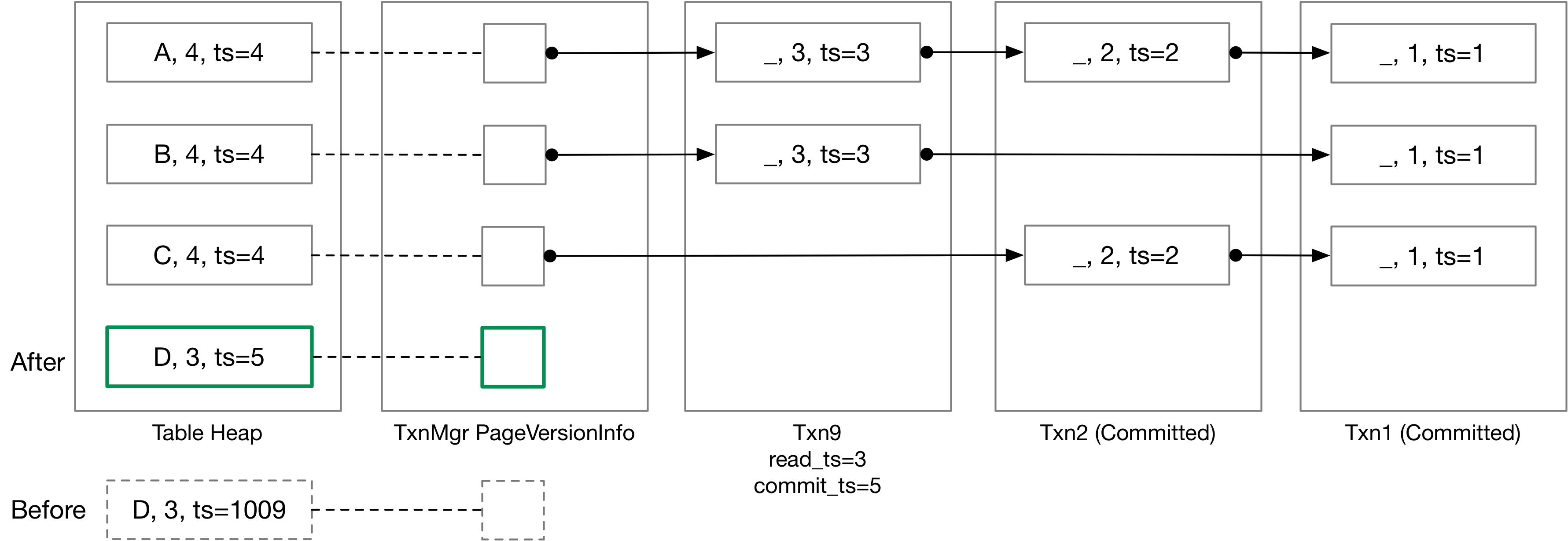

At this point in this project, your insert executor implementation should be nearly the same as in Project #3. You can simply create a new tuple in the table heap. You will need to correctly set the tuple metadata for the tuple. The timestamp in the table heap should be set to the transaction temporary timestamp, as described in Task 2.2. You do not need to modify the version link, and the next version link of this tuple should be nullopt, which indicates there are no previous versions for this tuple. You should also add the RID to the write set. The below figure is an illustration of txn9 inserting (D, 3) into the table.

In the starter code, we provide UpdateTupleInPlace and UpdateUndoLink / UpdateVersionLink to update the tuple in the table heap and the version link respectively. These functions will do an atomic compare-and-update operation, where you will need to provide a check function. The pseudo code for the two functions are as below:

UpdateVersionLink(rid, new_version_link, check_function) {

take the table heap lock / version link lock

retrieve the data from table heap / version link

call user-provided check function, if check failed, return false

update the data and return true

}

At this point, all test cases are single-threaded, and therefore you can simply pass a nullptr here as the check parameter to skip the check. Starting at Task 4.2, you may need to implement the check logic to detect write-write conflict when there are multiple threads updating a tuple and its metadata / version link concurrently.

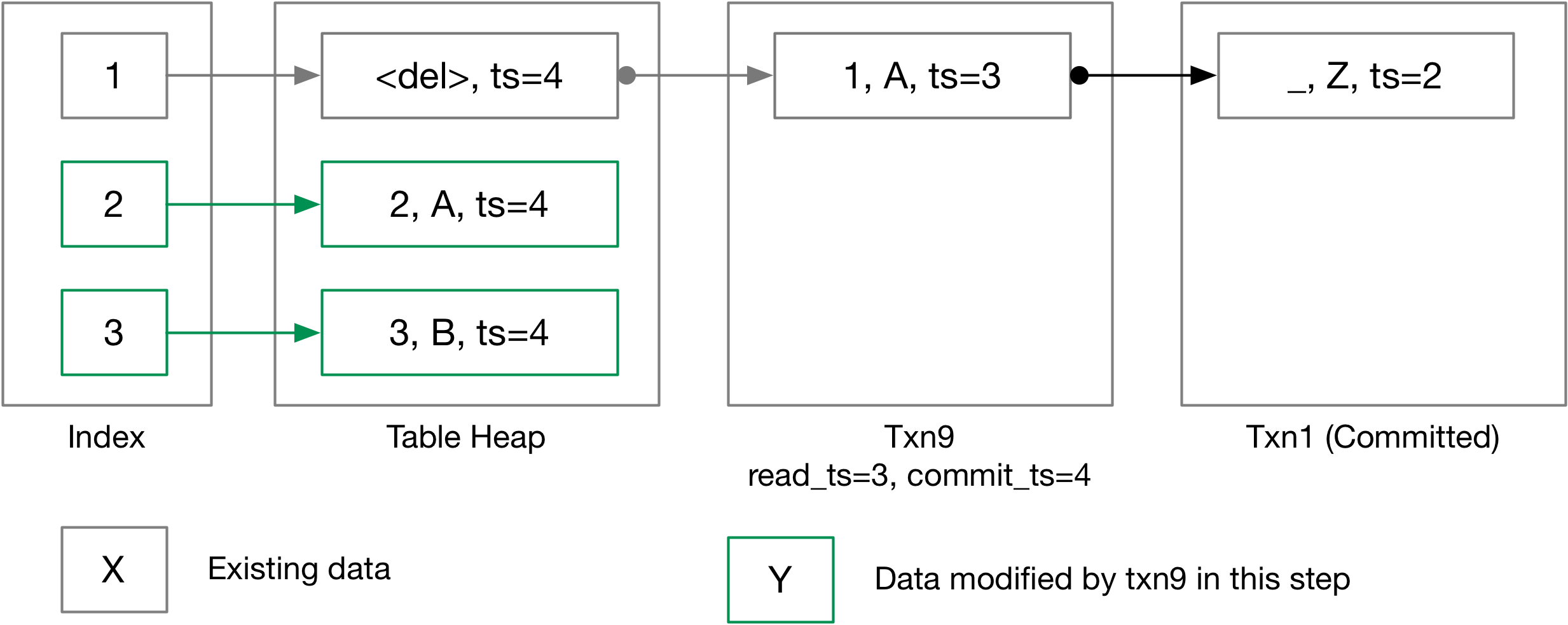

3.2 Commit

Only one transaction is allowed to enter the Commit function at a time, and you should ensure that by using commit_mutex_ in the transaction manager. In this task, you will need to extend your Commit implementation in the transaction manager with the commit logic. You should:

- Take the commit mutex.

- Obtain a commit timestamp (but not increasing the last-committed timestamp, as the content of the commit timestamp is not stabilized until the commit finishes).

- Iterate through all tuples changed by this transaction (using the write set), set the timestamp of the base tuples to the commit timestamp. You will need to maintain the write set in all modification executors (insert, update, delete).

- Set transaction to committed state and update the commit timestamp of the transaction.

- Update

last_committed_ts.

You should have implemented most of the above logic as a part of task 1, and you will need to add the iterating table logic.

We recommend you implement the debug function TxnMgrDbg that prints out the table heap content and the version chain. Our test cases will call your debug function after each important operation and you can print anything you want to examine the version chain.

Interactive Testing

You can use BusTub shell to test your implementation.

make -j`nproc` shell && ./bin/bustub-shell bustub> CREATE TABLE t1(v1 int, v2 int); bustub> INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3); bustub> \dbgmvcc t1 -- call your `TxnMgrDbg` function to dump the version chain bustub> BEGIN; txn?> INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (4, 4); txn?> \txn -1 bustub> SELECT * FROM t1; -- the newly-inserted row should not be visible to other txns bustub> \txn ? -- use the id you see before txn?> COMMIT;

You can also use the BusTub Netcat shell to start an interactive session with transactions.

You will need to install nc (netcat) in order to use this interactive shell.

make -j`nproc` nc-shell && ./bin/bustub-nc-shell bustub> CREATE TABLE t1(v1 int, v2 int); bustub> INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3); bustub> \dbgmvcc t1 -- call your `TxnMgrDbg` function to dump the version chain # in another terminal nc 127.0.0.1 23333 bustub> INSERT INTO t1 VALUES (4, 4); # in yet another terminal nc 127.0.0.1 23333 bustub> SELECT * FROM t1; -- the newly-inserted row should not be visible to this txn bustub> COMMIT;

And we provide the reference solution running in your browser at BusTub Web Shell.

Starting this task, all test cases are written in SQL. As long as your result of SQL query matches the reference output, you will get full points for a test case. We do not check the exact content of your version chain, except that we will check for number of undo logs and number of table heap tuples to ensure you are maintaining the version chain correctly.

3.3 Update and Delete Executor

In this task, you will need to implement the logic to generate undo logs, and to update the table heap tuples. The update and delete executor are basically the same (and you can implement the shared part in execution_common.cpp), where the update executor puts the new version of a tuple in the table heap, and delete executor sets the is_delete flag for a tuple in the table heap.

Before updating or deleting a tuple, you will need to check for write-write conflict. If a tuple is being modified by an uncommitted transaction, no other transactions are allowed to modify it, and if they do, it will be a write-write conflict and the transaction conflicting with a previous transaction should be aborted. Another write-write conflict case is when a transaction A deletes a tuple and commits, and another transaction B that starts before A and deletes the same tuple (writing to a tuple larger than read ts). The transaction state should be set to TAINTED when a write-write conflict is detected, and you will need to throw an ExecutionException in order to mark the SQL statement failed to execute (ExecuteSqlTxn returns false if there is an execution exception). At this point, we do not require you to implement the actual abort logic. The test cases in this task will not call the Abort function.

Your update executor should be implemented as a pipeline breaker: it should first scan all tuples from the child executor to a local buffer before writing any updates. After that, it should pull the tuples from the local buffer, compute the updated tuple, and then perform the updates on the table heap.

At this point, all test cases are single-threaded, and therefore you do not need to think hard about race conditions that might occur during the update / delete process. The only condition for detecting write-write conflict is to check the timestamp of the base tuple meta.

Let us go through the above example. In case (1), txn10 deletes the (A, 2) tuple and has not committed yet. Txn9 can still read an old version of the tuple (A, 2) because the read timestamp is 3.In this case, if txn9 needs to update / delete the tuple, it should be aborted with a write-write conflict In case (2), if any other transactions try to update / delete this tuple, they will be aborted. In case (3), there is another transaction that updates (C, 2) to (C, 4) and the commit timestamp is set to 4. Txn9 can read an old version of the tuple (C, 2), but it should be aborted when update / delete the (C, 4) tuple, because there is a newer update that happens after the transaction read timestamp.

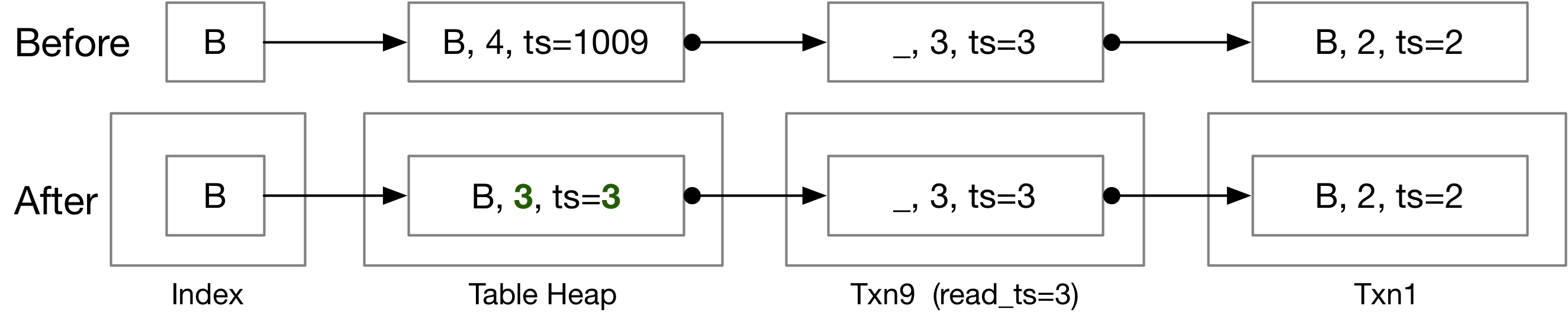

After checking the write-write conflict, you can proceed with implementing the update / delete logic.

- Create the undo log for the modification. For deletes, generate an undo log that contains the full data of the original tuple. For updates, generate an undo log that only contains the modified columns. Store the undo log in the current transaction. If the current transaction already modified the tuple and has an undo log for the tuple, it should update the existing undo log instead of creating new ones.

- Update the next version link of the tuple to point to the new undo log.

- Update the base tuple and base meta in the table heap.

The above figure illustrates what happens on a delete.

The above figure shows what happens on an update.

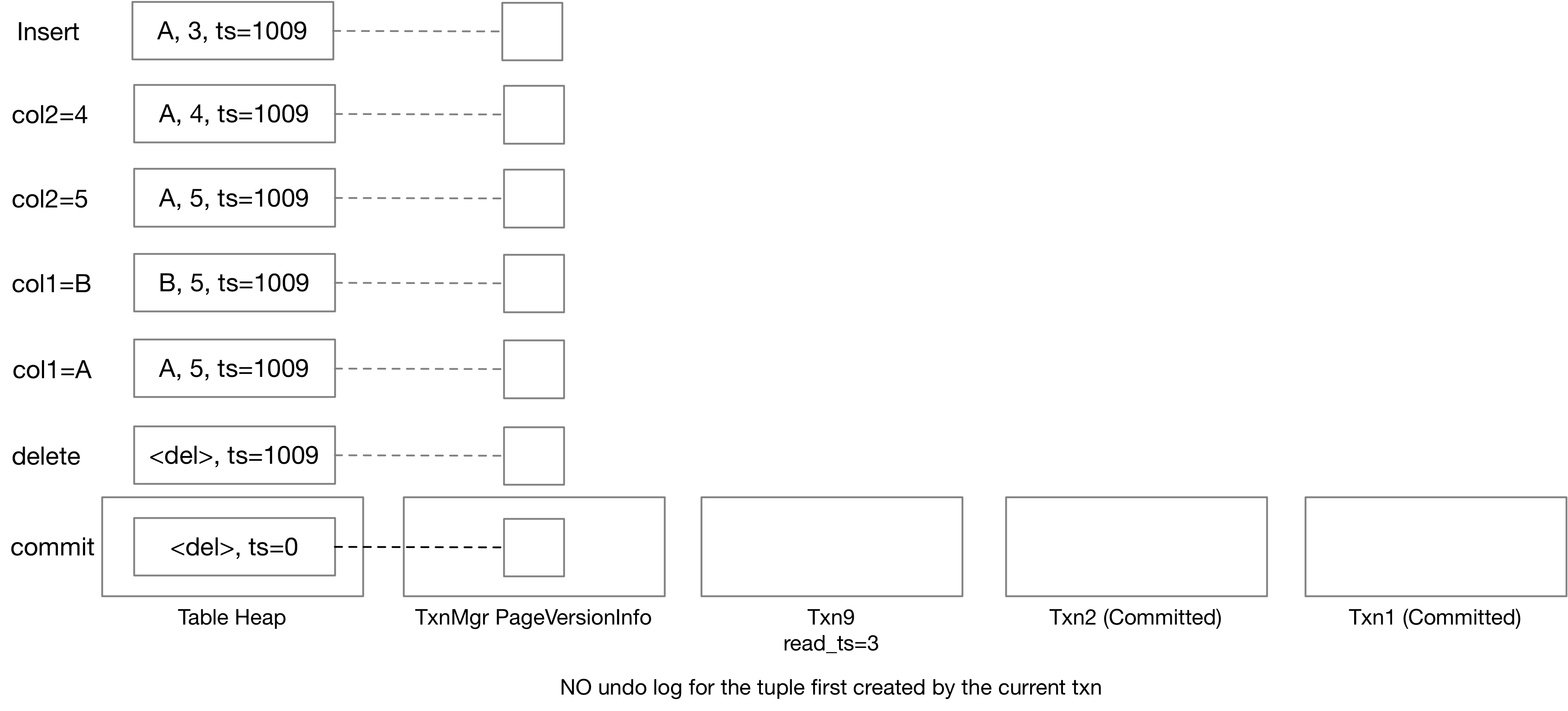

Your implementation also needs to consider self-modification, which should be done before checking write-write conflict. If a tuple has already been modified by the current transaction, it can be updated / deleted by itself and you should not regard this as write-write conflict. If the tuple is newly-inserted, no undo log needs to be created. Otherwise, a transaction holds at most ONE undo log for each RID. Therefore, if a transaction updates a tuple twice, you will need to update the previous undo log / only update the table heap.

In this example, txn9 first updates the tuple to (A, 4), then (A, 5), then (B, 5), then (A, 5), and finally deletes it. Throughout the process, txn9 keeps exactly one undo log for the entry. Note that when we update (B, 5) to (A, 5), though we can update the undo log back to a partial update (_, 5), we ask you to keep the undo log unchanged – only adding more data to undo log but not removing data, so as to make it easier to handle concurrency issues.

In the above example, txn9 inserts a tuple, makes several modifications, and then removes it. In this case, you can directly modify the table heap tuple without generating any undo log.

Note that we set the timestamp to 0 at the end because this tuple is inserted by txn9 and removed by txn9, which means that it never exists. If the version chain contains undo logs, it should be set to the commit timestamp so that the undo logs can be accessed with a transaction with lower read timestamp. You can also follow the usual commit logic to set the timestamp to the commit timestamp anyways. As long as you can read the correct data at each timestamp, this does not matter until Bonus Task #2.

You will find Tuple::IsTupleContentEqual and Value::CompareExactlyEquals useful when computing the undo log.

In this project, we will always use fixed-size types, and therefore UpdateTupleInPlace should always succeed without throwing an exception.

As we do not have an index at this point, and all tuples are identified solely using RID, the version chain will only have a deletion marker at the head (in the table heap). There will be no deletion markers in the undo log, because a tuple will not be re-created in the same place after deletion. Therefore, you can skip handling a lot of cases when generating the undo log.

To put everything together, for update / deletes, you should:

- Get the RID from the child executor.

- Generate the updated tuple, for updates.

- For self-modification, update the table heap tuple, and optionally, the undo log in the current transaction if there is one.

- Otherwise, generate the undo log, and link them together.

At this point, you should pass the TxnExecutorTest except the garbage collection test case.

Task 3.4 Stop-the-world Garbage Collection

In the starter code, once we add the transaction into the transaction map, we never remove it, because transactions with a lower read timestamp might need to read the undo logs stored in the previous committed or aborted transactions. In this task, you will need to implement a simple garbage collection strategy that removes unused transactions.

Garbage collection is triggered manually when GarbageCollection is called. The test cases will only call this function when all transactions are paused. Therefore, you do not need to worry too much about race conditions when doing garbage collection. In Task 1, we already implemented an algorithm to compute the watermark (the lowest read_ts in the system). In this task, you will need to remove all transactions that do not contain any undo log that is visible to the transaction with the lowest read_ts (watermark).

You will need to traverse the table heap and the version chain to identify undo logs that are still accessible by any of the ongoing transactions. If a transaction is committed / aborted, and does not contain any undo logs visible to the ongoing transactions, you can simply remove it from the transaction map.

The example above illustrates the case where the watermark timestamp is 3 and we have txn1, txn2, txn9 committed. Txn1’s undo logs are no longer accessible, so we can directly remove it. Txn2’s undo log for tuple (A, 2) is not accessible, but tuple (C, 2) is still accessible, so we cannot remove it right now. After removing txn1, there will be dangling pointers to a removed undo log buffer, as indicated in dashed lines. You DO NOT need to update the previous undo log to modify the dangling pointer and make it an invalid pointer, and it is fine to leave it there. If everything in your implementation is correct, your sequential scan executor will never attempt to trace these dangling pointers as they are below the watermark. However, we still recommend you to add some asserts in your code to ensure this will never happen.

At this point, you should pass the TxnExecutorTest.

Task #4 - Primary Key Index

BusTub supports primary key index, which can be created in the following way:

CREATE TABLE t1(v1 int PRIMARY KEY); CREATE TABLE t1(v1 int, v2 int, PRIMARY KEY(v1, v2));

When the primary key is specified when a table is created, BusTub will automatically create an index with its is_primary_key property set to true. One table will have at most one primary key index. Primary key indexes ensure uniqueness of the primary key. In this task, you will need to handle primary key indexes in your executors. The test cases will not create secondary indexes using CREATE INDEX, and therefore you do not need to maintain secondary indexes in this task.

4.0 Index Scan

You do not need to implement the MVCC index scan executor at this point. This is for Task 4.2 and above. Our test case will use range queries instead of equal queries to avoid the sequential scan to index scan rule being invoked, so that sequential scans will not be converted to index scans when you implement Task 4.1.

4.1 Inserts

You will need to modify your insert executor to correctly handle the primary key index. At the same time, you will also need to think about the case that multiple transactions are inserting the same primary key in multiple threads. Inserting with index can be done with the following steps:

- Firstly, check if the tuple already exists in the index. If it exists, abort the transaction.

- This only applies to Task 4.1. If you are going to implement Task 4.2, then it is possible that the index points to a deleted tuple, and in this case, you should not abort.

- You only need to set the transaction state to

TAINTEDin Task 4.TAINTEDmeans that the transaction is about to be aborted, but the data is not cleaned up yet. You do not need to implement the actual abort process. The tainted transaction will leave some tuple in the table heap, and you do not need to clean it up. When another transaction inserts to the same place and detects a write-write conflict, as the tuple is not cleaned up, it should still be regarded as a conflict. After setting the transaction toTAINTEDstate, you will also need to throw an ExecutionException so thatExecuteSqlwill return false and the test case will know that the transaction / SQL was aborted.

- Then, create a tuple on the table heap with a transaction temporary timestamp.

- After that, insert the tuple into the index. Your hash index should return false if the unique key constraint is violated. Between (1) and (3), it is possible that other transactions are doing the same thing, and a new entry is created in the index before the current transaction could create it. In this case, you will need to abort the transaction, and there will be a tuple in the table heap that is not pointed by any entry in the index.

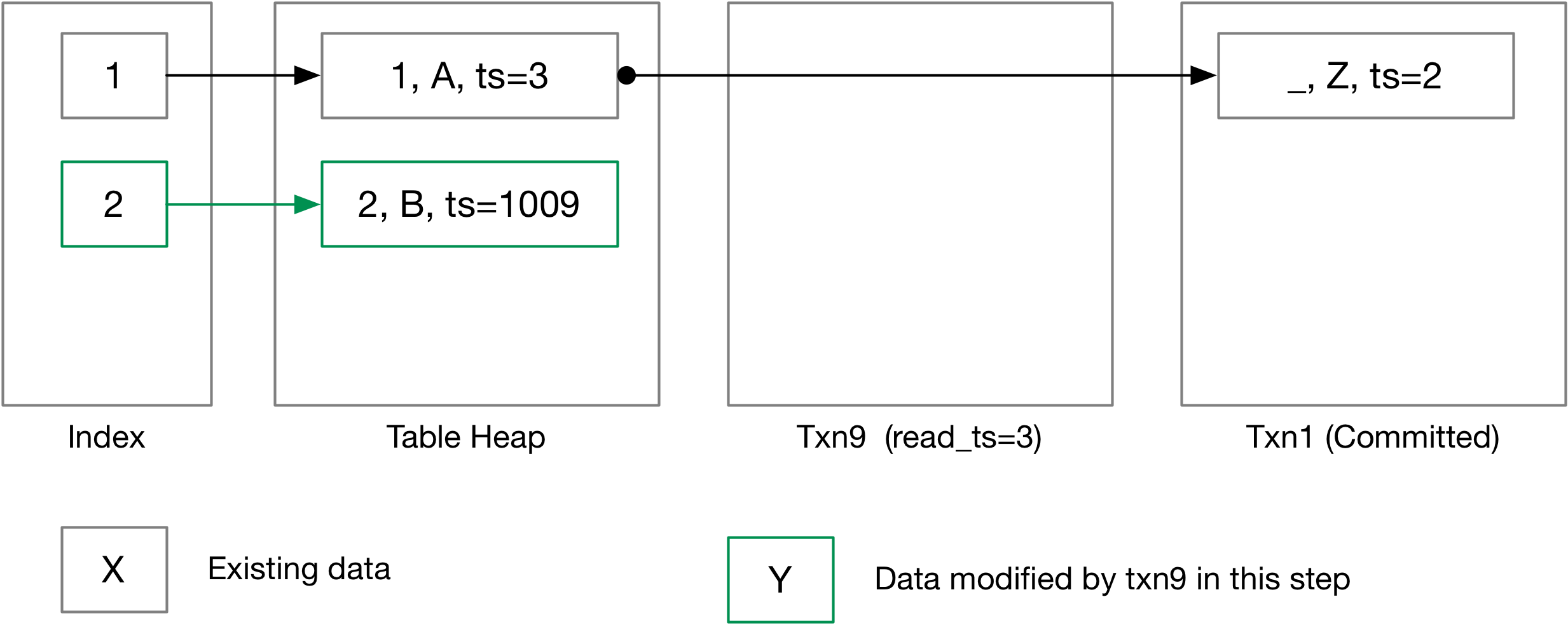

In this example, let us go through txn9 inserting A, B, C respectively. Assuming the first column of the tuple is the primary key. From this example, we will also not show the version page info structure in the figure any more.

- Inserting A: the key already exists in the index, violating the uniqueness requirement for primary key, thus aborting the transaction.

- Inserting B: as there is no conflict in the index, first create a tuple in the table heap, and then insert the RID of the newly-created tuple into the index.

- Inserting C: assuming there is another transaction 10 doing the same thing. Txn9 first detects no conflict in the index and creates a tuple in the table heap. Then, in the background, Txn10 does (2) and (3) that created a tuple and updated the index. When txn9 tries inserting into the index in step (4), there will be a conflict, and therefore txn9 should go into the tainted state.

At this point, we will have the first concurrent test case in this project, where we test if your implementation works correctly when multiple threads insert the same key.

4.2 Index Scan, Deletes and Updates

In this task, you will need to add index support for delete and update executor. You will need to first implement the multi-version index scan executor, and then implement updates and deletes support for insert, update, and delete executors.

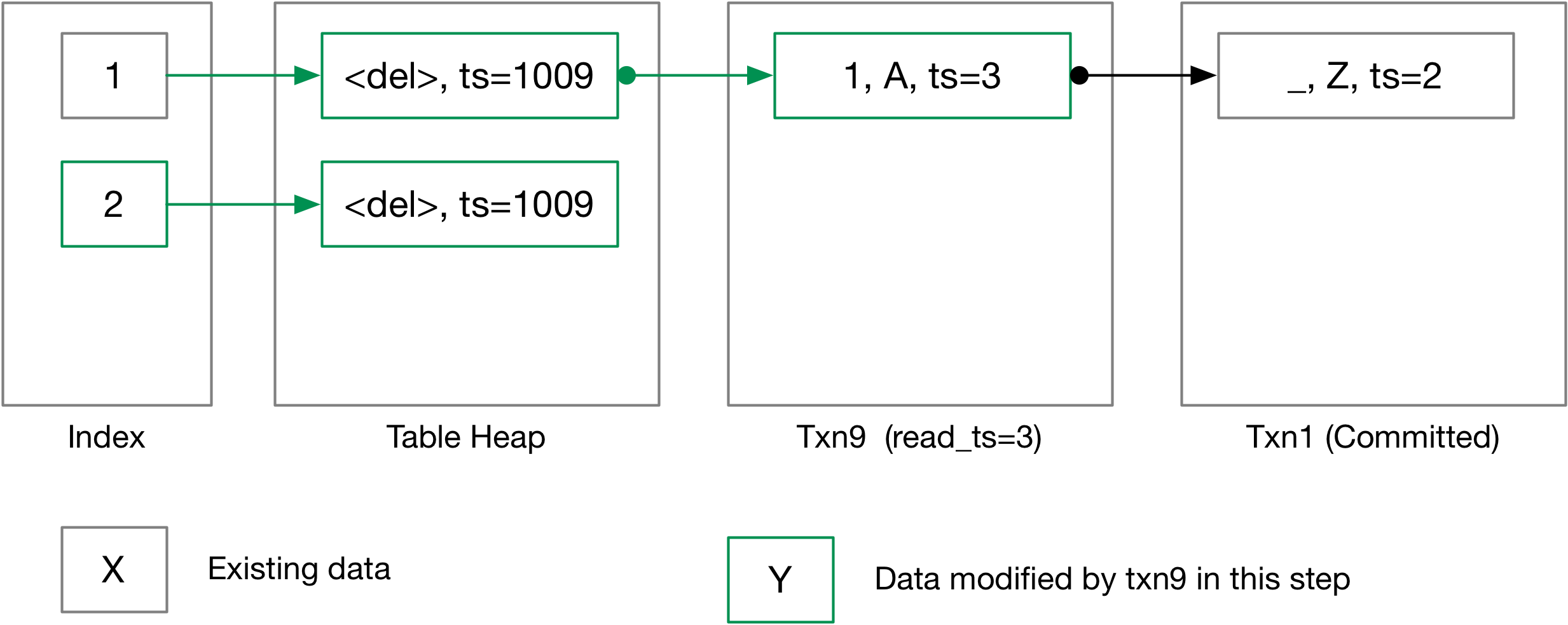

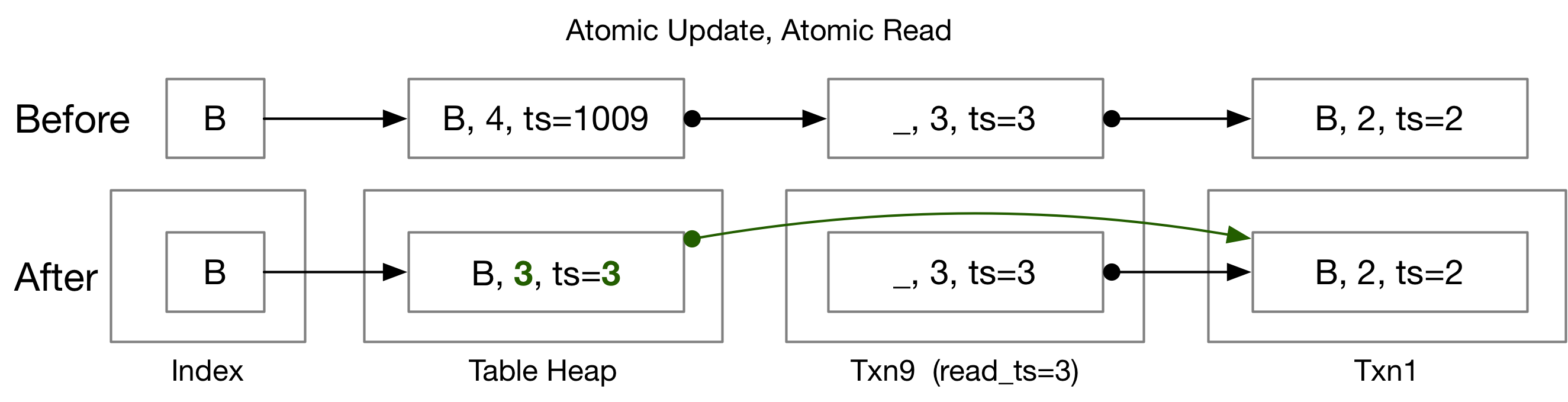

Once an entry is created in the index, it will always point to the same RID and will NOT be removed even if the tuple is marked deleted, so that an earlier transaction can still access the history with the index scan executor. At this point, you will also need to revisit your insert executor. Consider the case that insert executor inserts into a tuple which is removed by delete executor. Your implementation should update the deleted tuple instead of creating a new entry, because an index entry always points to the same RID once created. You will need to correctly handle the write-write conflict detection and unique constraint detection.

In this example, tuple (B, 2) has been deleted by txn1. We DO NOT remove the entry from the index when a tuple is deleted, and therefore the index may point to a deletion marker, and will ALWAYS point to the same RID once it is there. When txn9 inserts (B, 3) into the table with the insert executor, it should NOT create a new tuple. Instead, it should update the deletion marker to the inserted tuple, as if it is an update.

You will also need to think about other race conditions at this point. For example, if multiple transactions are updating the version link at the same time. You should correctly abort some of them and let one of them proceed without losing any data. In the version info page, we have the in_progress field that indicates if there is already an ongoing transaction on the tuple. From this task, you will need to use this field to avoid race conditions. Also, you will notice that at the second change in the above example, there will be a small amount of time when the table heap contains a tuple with the same timestamp as the first undo log. Your sequential scan executor should also handle this case correctly after you have implemented updates and deletes.

4.3 Primary Key Updates

One edge case of update with index is when the primary key gets updated. In this case, the update should be implemented as a delete on the original key and an insert on the new key.

Let us go through the case that we UPDATE table SET col1 = col1 + 1, where col1 is the primary key. Before we do the actual update, txn9 first inserts (2, B) into the table, as below.

Now we start updating the table set col1 = col1 + 1, where we first delete all tuples that will be updated and the primary key has changed.

Next, we insert the updated tuple back to the table.

And finally, commit the changes.

Bonus Task 1: Abort

This is optional. Before this task, transactions that go into the tainted state will cause other transactions to abort on the write-conflicting tuples. In this task, you are required to implement the abort logic, so that we can continue modifying the tuples when any of the transactions aborts. Remember that we detect write-write conflict by checking if there is an ongoing modification to a tuple. When aborting a transaction, we should revert this change, so that other transactions can write to the tuple.

You will need to choose your own adventure in this task.

Implementation #1

In this example, we are going to abort txn9. You can simply undo the tuple and set the table heap to the original value. This is easier to implement and will leave your version chain with two items with timestamp 3. Your sequential scan / index scan executor should correctly handle this situation after the transaction is aborted.

With this implementation, aborted transactions will have undo logs in the version chain, and cannot be immediately reclaimed in garbage collection.

Implementation #2

In this example, aborting txn9 will atomically link the version link to the previous version and update the table heap. You will need to acquire both table lock and the version link lock at the same time whenever you modify them or read them. With this implementation, you do not need to wait until the watermark before removing the aborted transaction from the transaction map. However, you will need to refactor all the places where you get the version link to use the new locking mechanism. With this locking mechanism, you likely do not need the in_progress_ field any more in the version link.

You can manually acquire table heap locks by using TableHeap::AcquireTablePage{Read|Write}Lock, modify the table heap with lock held by using TableHeap::UpdateTupleInPlaceWithLockAcquired, and get the tuple using TableHeap::GetTupleWithLockAcquired etc. DO NOT use the normal TableHeap::UpdateTupleInPlace and TableHeap::GetTuple function as it will also acquire the lock and causing deadlock in your code. Note that acquiring the same read lock twice in one thread will also cause deadlock when there is a writer.

If the transaction inserts a fresh new tuple without undo logs, the abort process simply sets it to a deletion marker with ts = 0. The commit timestamp in BusTub starts from 1, and therefore setting it to 0 will be safe.

You do not need to revert index modifications. Anything added to the index will stay there and will not be removed. You also do not need to actually remove a tuple from the table heap. If you need to revert an insertion, simply set it to a deletion marker.

You should allow multiple threads aborting in parallel. That is, do not take the commit_mutex or any other locks throughout the whole function.

Bonus Task #2 - Serializable Verification

This is optional. If a transaction runs in serializable isolation level, you will need to verify if it satisfies the serializability when committing the transaction. We use OCC backward validation for serializable verification. Note that the verification method we talked about in the lecture only applies to a static database. In BusTub, you will need to consider newly-inserted and deleted records. To complete the serializable verification, you will need to store the scan filter (aka. scan predicate) in the transaction each time the sequential scan executor or the index scan executor are called. You will also need to track the write set correctly. With all the information, we can do serializable verification by checking if the scan predicate (read set) intersects with the write set of transactions that starts after the current transaction starts, as follows when we commit a transaction:

- You do not need to verify a read-only transaction.

- Collect all transactions that commits after the read timestamp of the current transaction. We call these “conflict transactions”.

- Collect all RIDs that are modified by conflict transactions.

- For each tuple, iterate through its version chain to verify if the current transaction reads any “phantom”. You can collect all undo logs up to the transaction read timestamp. Then, replay it one by one to check the intersection.

- For each update in the version chain,

- For insert, you should check if the new tuple satisfies any of the scan predicates of the current transaction. If yes, abort.

- For delete, you should check if the deleted tuple satisfies any of the scan predicates of the current transaction. If yes, abort.

- There is an edge case where a transaction inserts and then removes a tuple, which leaves a delete marker in the table heap. This should be regarded as a no-op instead of a delete.

- For update, you should check both the “before image” and the “after image”. If any of them overlaps with any of the scan predicates of the current transaction, abort.

- Consider the case that a transaction modifies a tuple but then reverts it back, which leaves an undo log that updates some columns to the same value. In this case, you should still process it as an identical update instead of ignoring it, and abort the transaction if necessary.

- However, if there are two transactions, where the first one modifies the value from X to Y, and then, the second one, Y to X, you should still detect the conflicts that X is changed, if there is a txn3 starting before txn1 starts and committing after txn2 commits.

If a transaction needs to be aborted in the commit phase, you should directly go through the abort logic to revert the changes, and set the transaction status to ABORTED instead of TAINTED.

This verification method is inefficient because (1) only one transaction can enter the verification process (2) we loop over all write sets of possible-conflicting transactions and evaluate scan predicates on that. You may consider implementing parallel verification, or precision locking (attribute-level checking instead of checking the record), in leaderboard tests.

To test your implementation using BusTub shell,

./bin/bustub-shell bustub> set global_isolation_level=serializable;

For BusTub Netcat shell,

./bin/bustub-nc-shell --serializable

Leaderboard Benchmark - T-NET, the Terrier NFT Exchange Network

In a galaxy far, far away, there is a universe in which Jack Russell terriers live in a highly-civilized society. We say that the society is highly civilized, except that NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are becoming increasingly popular. One day, the terriers decide to find a database system to track their NFTs, and BusTub is one of their candidate systems.

Benchmark #1 - Token Transfer over T-NET / Snapshot Isolation

Terriers transfer their NFTs over T-NET. T-NET works like bank transfers: one terrier can initiate a transfer of a number of NFTs to another terrier. For this scenario, the transactions will be running in snapshot isolation mode.

CREATE TABLE terriers(terrier int primary key, token int); -- each transaction: transfer A tokens from X to Y UPDATE terriers SET token = token + A WHERE terrier = X; UPDATE terriers SET token = token - A WHERE terrier = Y;

Benchmark #2 - Trading-Network over T-NET / Serializable

When transferring NFTs on T-NET, terriers will be charged for transfer fees. The transfer fees will be waived if two terriers are on the same trading network. The network is represented by an integer ID.

CREATE TABLE terriers(terrier int primary key, token int, network int); -- each transaction: transfer A tokens from X to Y X_network = SELECT network FROM terriers WHERE terrier = X; Y_network = SELECT network FROM terriers WHERE terrier = Y; UPDATE terriers SET token = token + A * 0.97 WHERE terrier = X; -- if X_network != Y_network UPDATE terriers SET token = token + A WHERE terrier = X; -- if X_network == Y_network UPDATE terriers SET token = token - A WHERE terrier = Y;

At the same time, terriers can invite others to join their network with a sign-on bonus:

-- X invites Y to join the network A = SELECT network FROM terriers WHERE terrier = X; UPDATE terriers SET network = A, token = token + 1000 WHERE terrier = Y;

Terriers can also start their own network with a network registration fee.

-- X starts a new trading network UPDATE terriers SET network = ?, token = token - 1000 WHERE terrier = X;

All transactions in this benchmark will run at serializable level.

Due to how T-NET works, it is possible that a terrier can own a negative amount of NFTs.

You might need to implement a more fine-grained garbage collection when sequential scan is running or on transaction commit / abort. The leaderboard test will not call the stop-the-world garbage collector you have implemented in Task 3. Note that some of our test cases need to access commit_ts after commit, and therefore you can clear the undo buffer instead of removing the transaction from the map when doing fine-grained garbage collection instead of removing it as in stop-the-world garbage collection.

Implementing a more efficient serializable verification (i.e., precision locking) might be helpful in leaderboard benchmarks. It might also be helpful to implement parallel serializable verification.

You will be ranked on speed of transfers and space usage of the database system respectively. The speed of transfers is measured by the throughput of the system, and the space usage is measured by the total number of rows in table tuples and undo logs in the system. There will be a background thread collecting number of rows in the system periodically, and the space usage is computed with the maximum number of rows at any time throughout the benchmark. The final leaderboard bonus score will be computed as: min{speed_rank_bonus+space_rank_bonus, leaderboard_maximum_bonus}. For each ranking, you will get 15 points for the 1st place, 10 points for 2nd-10th place, and 5 points for 11th-20th place.

Leaderboard Policy

- Submissions with leaderboard bonus are subject to manual review by TAs.

- By saying "review", it means that TAs will manually look into your code, or if they are unsure whether an optimization is correct or not by looking, they will make simple modification to existing test cases to see if your leaderboard optimization correctly handled the specific cases that you want to optimize.

- One example of simple modification: change the buffer pool manager size for the benchmark.

- Your optimization should not affect correctness and should be reasonable. You can optimize for specific cases, but it should work for all inputs in your optimized cases.

- Allowed: only handling 3-table join reordering in Fall 2022 Project #3.

- Allowed: optimize for leaf node size > 100 in Project #2.

- Disallowed: compare the plan with the leaderboard test and convert it to ValueExecutor with the output table in Project #3. That’s because your optimization should work for all table contents. Hardcoding the answer will yield wrong result in some cases.

- Specifically for this project, you are not allowed to stall the system so that your system has a super low throughput while having a low space usage (there are only a few updates). You are not allowed to use a global lock to serialize all transactions in order to reduce the number of write-write conflicts. We will dump some data at the end of benchmark, and TAs will look into the data to find such violations. Your performance should be reasonable compared with reference solution in order to get a bonus for the space usage rank.

- You should not try detecting whether your submission is running leaderboard test by using side information.

- Unless we allow you to do so.

- Disallowed: use

#ifdef NDEBUG, etc.

- Submissions with obvious correctness issues will not be assigned leaderboard bonus.

- You cannot use late days for leaderboard tests. For this project, you may use late days for bonus tasks.

- If you are unsure about whether an optimization is reasonable, you should post on Piazza or visit any TA's office hour.

Appendix

In the appendix, we provide a list of files you will likely need to modify in this project:

- transaction_manager.h / transaction_manager.cpp

- execution_common.h / execution_common.cpp

- seq_scan_executor.h / seq_scan_executor.cpp

- index_scan_executor.h / index_scan_executor.cpp

- insert_executor.h / insert_executor.cpp

- update_executor.h / update_executor.cpp

- delete_executor.h / delete_executor.cpp

- watermark.h / watermark.cpp

And a list of functions / classes that might be helpful in this project:

- TableHeap: MakeIterator, GetTuple, GetTupleMeta, UpdateTupleMeta, UpdateTupleInPlace, MakeIterator, MakeEagerIterator; Bonus Task 1 and beyond, everything with

Lock. - Tuple: SetRid, GetRid, schema + vector

constructor, Empty, IsTupleContentEqual, GetValue. - Value: ValueFactory::GetSomething() ,ValueFactory::GetNullValueByType, CompareExactlyEquals.

- Schema: GetColumn, GetColumnCount.

- TransactionManager: UpdateUndoLink, GetUndoLink, GetUndoLog, GetUndoLogOptional; Task 4.2 and beyond, UpdateVersionLink, GetVersionLink.

- VersionUndoLink. UndoLink, UndoLog, Transaction (all member functions are important).

- You might need to frequently map an optional value to something else. You may use the following syntax to write more concise code:

auto x = opt.has_value() ? operation(*opt) : std::nullopt;. - Using C++14 tuple unpacking syntax might be helpful, i.e.,

auto [meta, tuple] = iter->GetTuple();. - Using initializer list might be helpful, i.e.,

VersionUndoLink{undo_link}automatically sets thein_progressfield to befalse.

Instructions

See the Project #0 instructions for how to create your private repository and set up your development environment.

You must pull the latest changes from the upstream BusTub repository for test files and other supplementary files we provide in this project.

Memory Leaks

For this project, we use LLVM Address Sanitizer (ASAN) and Leak Sanitizer (LSAN) to check for memory errors. To enable ASAN and LSAN, configure CMake in debug mode and run tests as you normally would. If there is memory error, you will see a memory error report. Note that macOS only supports address sanitizer without leak sanitizer.

In some cases, address sanitizer might affect the usability of the debugger. In this case, you might need to disable all sanitizers by configuring the CMake project with:

$ cmake -DCMAKE_BUILD_TYPE=Debug -DBUSTUB_SANITIZER= ..

Development Hints

You can use BUSTUB_ASSERT for assertions in debug mode. Note that the statements within BUSTUB_ASSERT will NOT be executed in release mode.

If you have something to assert in all cases, use BUSTUB_ENSURE instead.

We encourage you to use a graphical debugger to debug your project if you are having problems.

If you are having compilation problems, running make clean does not completely reset the compilation process. You will need to delete your build directory and run cmake .. again before you rerun make.

Post all of your questions about this project on Piazza. Do not email the TAs directly with questions.

Grading Rubric

Each project submission will be graded based on the following criteria:

- Does the submission successfully execute all of the test cases and produce the correct answer?

- Does the submission execute without any memory leaks?

Late Policy

See the late policy in the syllabus.

Submission

After completing the assignment, submit your implementation to Gradescope for evaluation.

Running make submit-p4 in your build/ directory will generate a zip archive called project4-submission.zip under your project root directory that you can submit to Gradescope.

Remember to resolve all style issues before submitting:

make format make check-clang-tidy-p4

Collaboration Policy

- Every student has to work individually on this assignment.

- Students are allowed to discuss high-level details about the project with others.

- Students are not allowed to copy the contents of a white-board after a group meeting with other students.

- Students are not allowed to copy the solutions from another colleague.

WARNING: All of the code for this project must be your own. You may not copy source code from other students or other sources that you find on the web. Plagiarism will not be tolerated. See CMU's Policy on Academic Integrity for additional information.